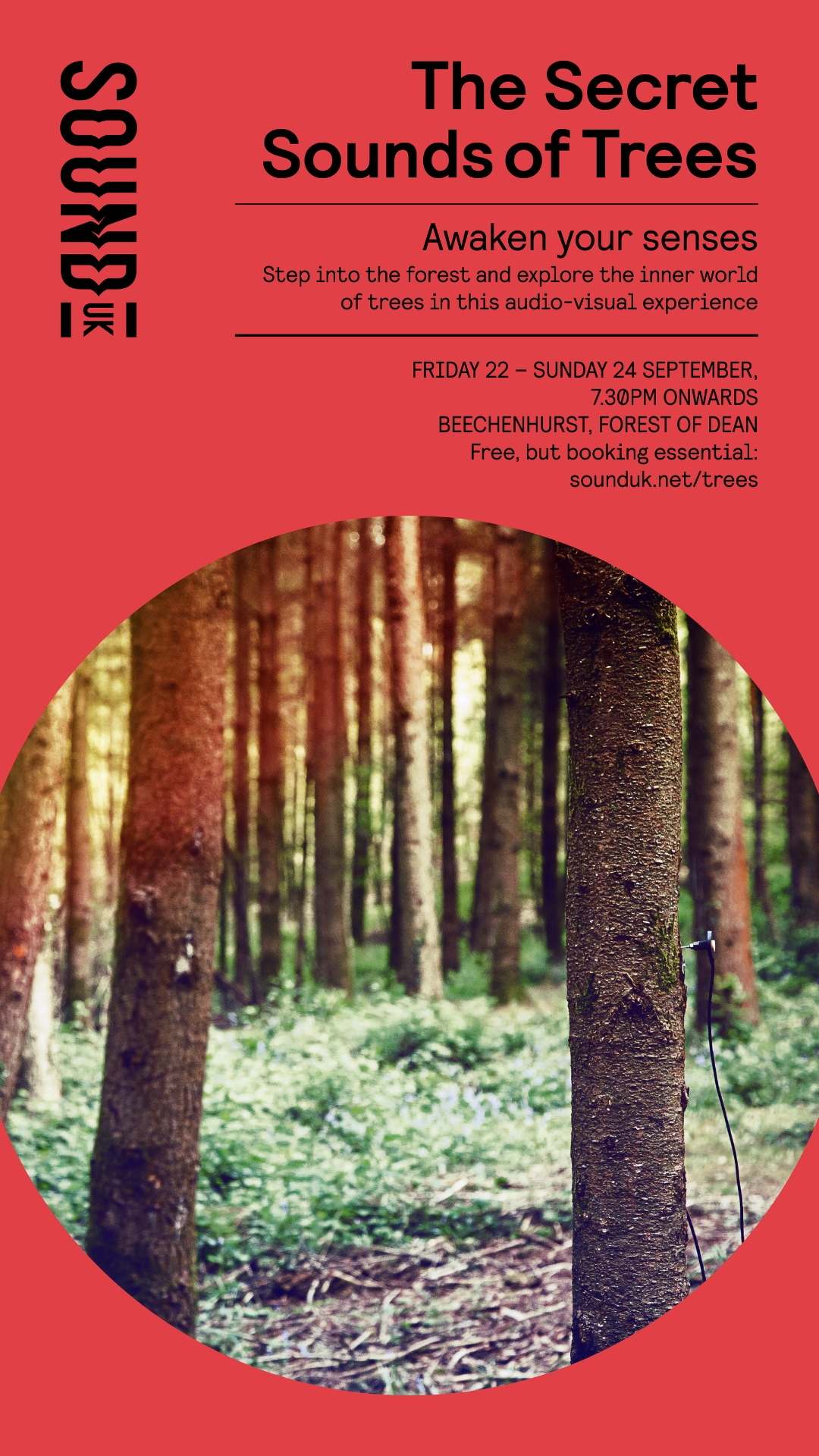

The Secret Sounds of Trees

September 22nd-24th 2023

Forest of Dean, UK

A soundwalk is also now available, with additional music by Lau Nau & narration, guiding you through some of the sounds such as sap, bark, xylem cells, roots, moss & mycorrhizal networks.

thanks to @pheobelaw & Maureen French

[press release]

Sound UK Arts invite you to step into the forest and explore the inner world of trees in a new audio-visual experience at Beechenhurst in the Forest of Dean. Discover the sounds of Beechenhurst’s trees, plant life, soil and insects.

An atmospheric soundscape, feathered, pink botanic, by acclaimed artists;

Jez riley French

and

Lau Nau

will immerse you in a hidden world, revealing microscopic vibrations and secret sounds inaudible to the human ear. Combined with lighting by leading artist Ulf Pedersen, we invite you to experience Beechenhurst in a totally new way.

The Secret Sounds of Trees is a timed entry installation from twilight through the evening. Free but booking essential.

Visit www.sounduk.net/trees for full details.

Commissioned and produced by Sound UK. Funded by Arts Council England and PRS Foundation. In partnership with Forestry England.

interview on recording the forest (part one);

In September 2023 we invite audiences to step into the Forest of Dean and explore the inner world of the trees in a new audio-visual experience, The Secret Sounds of Trees.

This month we caught up with sound artist Jez riley French to learn about his creative process, find out about some of the sounds he has recorded for this installation and how he is working with composer Lau Nau on this soundscape.

Can you tell us about your creative process for this new soundscape and your time capturing sounds at Beechenhurst?

My practice involves working with what I tend to refer to as sound outside of our attention and a key part of this is developing specialist microphones and techniques for listening in different ways, for example to the internal sounds of plants.

My interest is in the listening itself, and how accessing these sounds allows us to re-think the narratives around our perception of place.

When I’m able to spend some time in a specific location, such as at Beechenhurst, I’m not interested in ‘sound collecting’ as a flat, technical process. Instead I spend the time engrossed in the listening itself, including through the microphones I build, and every now and then, if it feels right, I’ll press record.

I think you have to be happy to let sounds go, to not always try to document them as it can, if that is the only motivation, interrupt the listening. It’s perhaps subtle, but for me that is how I keep a creative connection to the act of listening. It’s an intuitive process, guided of course by research and creative impulses, but the personal, moment to moment experience is what has allowed me to question standard ways of both listening and recording, and in so doing, extend the practice.

_large.jpg)

For Feathered Pink Botanic, the sound piece that is part of The Secret Sound of Trees, I focused on the internal sounds of trees, moss, ferns and in soil horizons beneath the forest floor.

The material itself then takes time to reflect on, re-listen to and start to gain a sense of how a piece might form from it.

When I do record something it tends to be a durational process, often spending several hours listening to a single sound or a wider location as it evolves. So listening back can also take a long time. It’s a gradual process; some days you have to step back, wait, and come back to a recording with fresh ears, find new ways for it to work in a piece.

As the installation for Beechenhurst is multi-channel, involving spatialisation, it’s only completed when we’re back there, working with speaker placement and the environment itself of course.

How have you collaborated with Lau Nau to create this soundscape?

I’ve known Laura (Lau Nau) for many years now and one thing that I find interesting about her work is that it uses melodic material in ways that pull you in to the music with apparent ease but without compromising its strength.

As with any collaboration there’s an important element of trust involved of course, and I think that’s been there since the first time we worked together. This means we can each connect to the material being shared with more of the ‘space’ that is needed.

Laura is based in Finland so we’ve been sending each other recordings and talking through ways to maintain the central point of the piece, which is to reveal the forest in a way that invites as wide an audience as possible to listen differently, connecting in new ways to the other species around them.

Can you tell us about some of the sounds of nature that we will hear within your new soundscape?

Describing the sounds in the piece is difficult, partly because many of them have not been recorded before.

The wider research is still catching up with these forms of listening and recording, and, to be honest, it’s not always clear what process is making the sounds. The cellular processes as plants draw in nutrients, or the microscopic signals in mycorrhizal / mycelium networks are all part of the work.

I think we’re also at a point now where we need to think carefully about how the language we use when talking about non-human life carries with it a degree of imposition, often unintentional but with some weight. That might seem overly senstive to some, but considering these questions is part of the responsibility we have when, in effect, we are using the sounds of other species as creative material.

What I can say though is that audiences will hear root systems taking in moisture, bark crackling as sap rises, the intricate sound of water storage in the moss blanketing the forest floor, insect activity and other vibrations in soil horizons (different layers of soil).

Is there a sound you captured that has really surprised you?

I’m always surprised, which is why I’m still finding new ways to listen, still fascinated.

Sometimes I might have a basic idea of the possible sounds from specific sources. For example the resonance of a building vibrating in its locale, or the root systems of plants early in the morning, but the point really is that these sounds never repeat and every inch of every environment is different, if you listen at the micro-level, even to vast landscapes.

The myriad combinations of sounds are always new, always evolving, so I’m constantly surprised. Constantly realising how much we can get from listening, and how much we still have to learn about what we hear, and how we translate the experiences.

_large.jpg)

How has listening to the forest affected you? Can you describe your experience of listening to the forest?

Listening, if you give it time, can be transformative to ones sense of place, and across the scale; from being immersed in a single sound source, to perceiving more and more of all the sounds around us at any given time, and of course, to aspects that signify less positive change.

At Beechenhurst, and in other forests over the past four or five years, I’ve noticed a quite radical drop in insect activity for example. Of course there is also the now constant sound of flight paths and traffic nearby.

I know such sounds frustrate some listeners, but it is what is there and if, like me, you reject the divide that the word ‘nature’ implies, separating the human species from all others, then those sounds are ‘nature’ sounds also, it’s just that they are made by one species without consideration of any other.

I find thinking about such sounds in that way gives one a sharper sense of our impact. That said, listening to species sounds below the surface, without those human sounds is a remarkable experience, and that is what The Secret Sounds of Trees will allow the audience to do.

How would you like audiences to approach this experience? And what do you hope audiences will take away from this experience?

To get the most from this, or any listening experience, the key really is to give time and space to the listening. That sounds obvious, simple, but as a species we’re generally not that good at listening.

We tend to try to occupy the space we are in, physically and sonically, even if we think we’re being quiet. So find a comfortable position in the area of the forest the event will be taking place in and realise that being there means you are part of the piece also.

The willingness to let all the other sounds have priority for a while will, hopefully, give each person a more meaningful experience, shared with everyone else there and of course, the forest itself. It’s important to remember also that we are encroaching on all the other species, and accepting that can help with the listening, with finding space to listen.

Any tips for audiences on how to listen deeply during the installation?

It does tend to be different for each person, but I think with events such as this, where we’re not on our own, the key is to be aware of your individual role in the collective quietness that will enhance the experience. Allow time for the sounds to take us beyond our usual, short attention spans.

Deep, or active listening, at its core is really about allowing the place or situation to guide the process. You have to give up control in a way. At least give up the idea that you know what a forest sounds like in this instance.

For this specific location we are providing straw bales to help the experience. Not many of use can stay totally still whilst standing for more than a few minutes.

How does being at Beechenhurst make you feel?

I tend to think, as I’ve already alluded to, that how we feel about a specific place takes time, and it should take time. I hadn’t visited this part of the forest before this project so I’m still processing my impressions, but, given that I was there specifically to listen, it did take me a couple of days to find my feet so to speak.

I think that’s one of the positive things about accessible spaces like Beechenhurst; you can go for a few hours or a day, but you can also keep returning and the closer you look, and listen, the more there is. Personally, if I keep returning to a place I have to allow it to influence my reason for doing so. Not to return with expectations, but with an understanding that I, we, have to do something more than use environments for our pleasure.

I spent some time around the borders of Beechenhurt also, thinking about the tension there is for any artist working in such places. We bring ourselves, our equipment and, hopefully, more people to them at times, but with work such as The Secret Sounds of Trees there is an important element of allowing audiences in to the sensory world of other species that isn’t normally accessible, so there is the artistic value but also a wider purpose that links to environmental knowledge and respect.