some articles and interviews. those that are still available online can be accessed by clicking the links

to un-write

false borders

to write about not writing

to leave blank space, avoid translation of place

ownership through imposed language

a dissolution of non-human realms

intuitive equity

writing;

feel'd recordings (coming soon)

sour is not a sour tasting word (Paradise Air residency activities)

YokAI + conversations with Chat GPT

Sawako Kato 1978-2024 (The Wire)

audible silence - a personal reflection on listening to sounds outside of our attention

Safe Space and the Male Field Recordist

interview in Lisbon SOA book

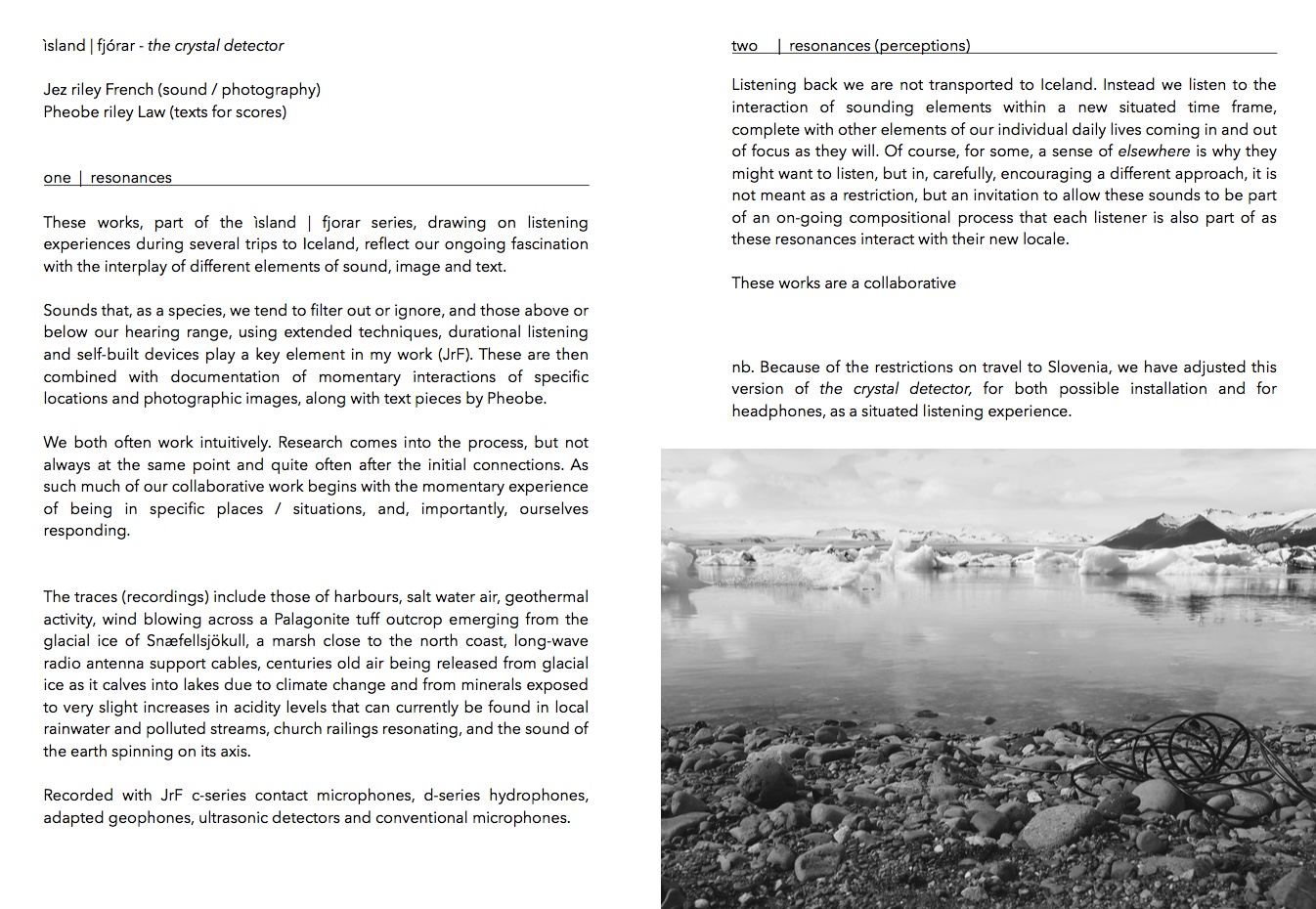

ísland | fjórar - the crystal detector | resonances (between perception and materiality)

Picked Raspberries, Jam and Listening to Buildings

Expanded Listening for Drawing Room (contribution)

Rowan Forestier-Walker 1977-2021 (The Wire)

Migration between Nature and Listening

Listening > Sound Art > Cinematic Distortion (of the act of listening and the pandemic)

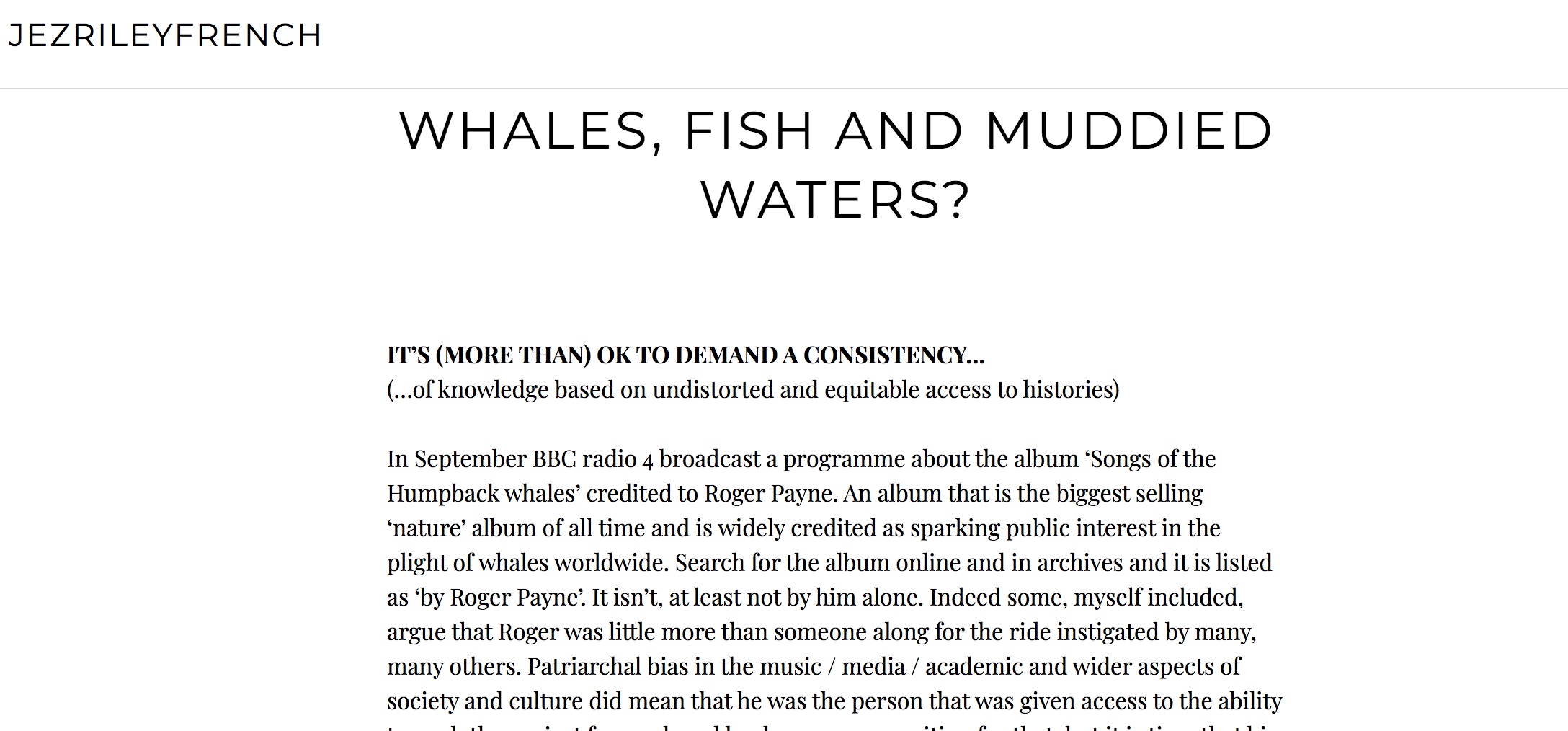

Whales, Fish and Muddied Waters?

scores for listening - Os Pressan #4

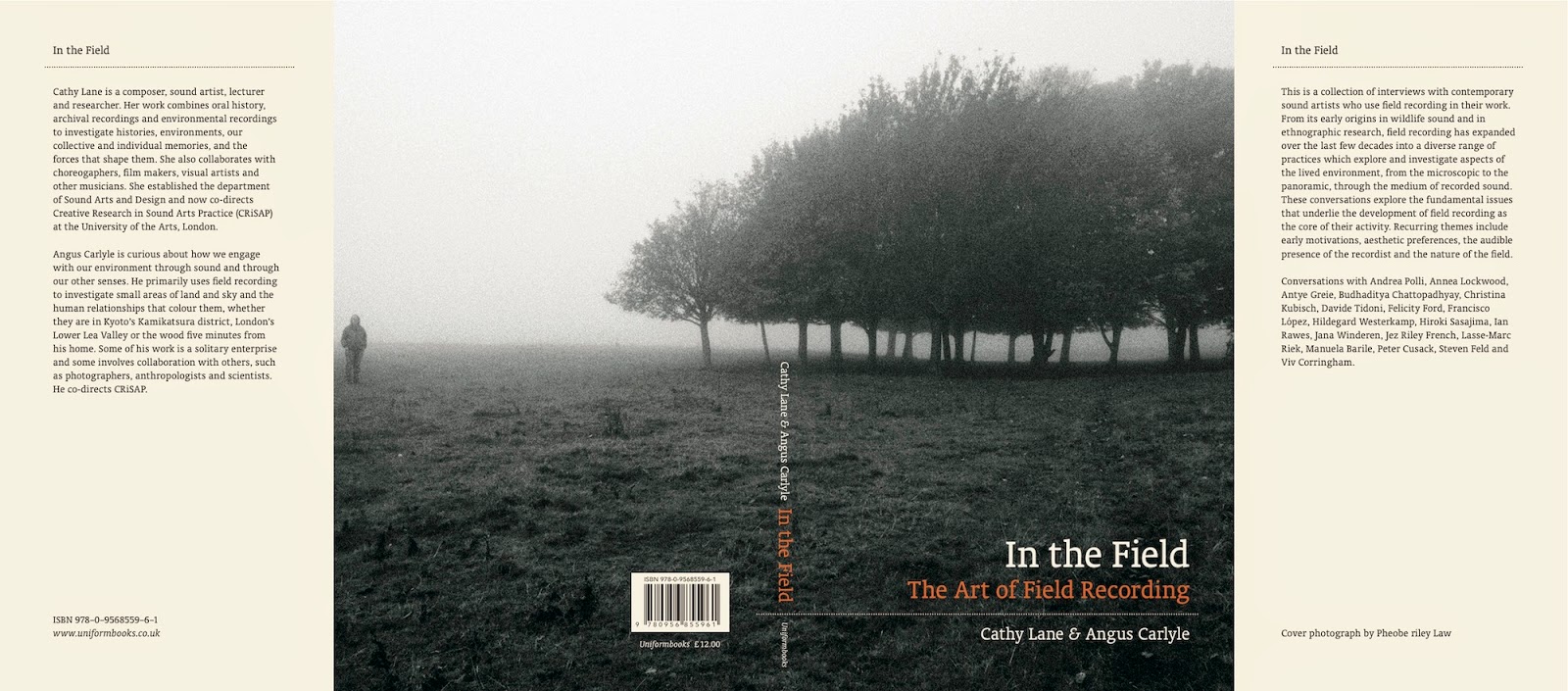

'Expanded Listening' by Aura Satz (inc. collaborative text by myself & Pheobe riley Law)

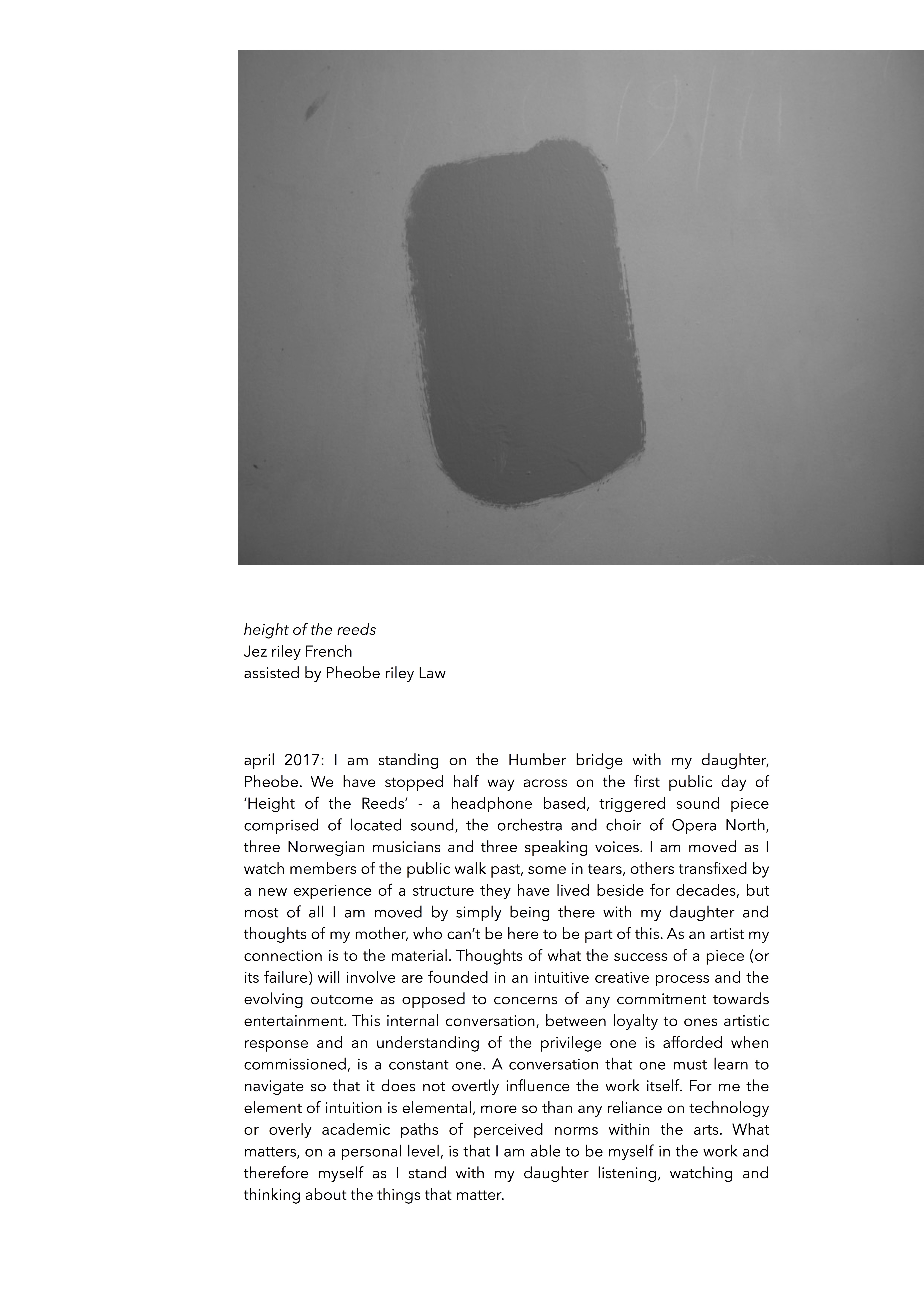

Height of the Reeds (Sonic Ideas Journal)

Scores for Listening (Robida)

Tate Modern - Sleeping & Waking (exhibition catalogue)

A Piece of Chalk (British Library)

A Closer Relationship with Listening (New York Public Library)

A Quiet Position - Polyphonies (for British Library / CBtR)

articles / interviews;

Under the Spell of the Sensuous

Recording the Forest

part one

A Journey in Sound; BBC Scotland podcast

part one

part two

Life of Listening (Bandcamp Daily)

Elusive Fields / Verdure Engraved review (The Wire)

on Score and Sound, Ethics and Aesthetics (Sunday Tribune)

British Library Archive Interview

part one

part two

Democratic Sound - the C-Series Contact Microphone

Matters of Duration (Scores for Listening) (Source Photographic Review)

Punkt Festival Performance Review (All About Jazz)

Ear Room (Sound and Music)

The Epiphany of Sound through Objects (Inframedia)

tierce (Another Timbre)

I have an article published as part of World Listening Day 2021; a personal reflection on listening to sounds outside of our attention;

…hearing the timbers of home creak at night. A low tone, humming from my bedroom wall; the washing line, moored to the outside wall feet below the window.

house cooling

home warming again in the morning, further, quieter shifts.

https://www.worldlisteningproject.org/audible-silence-a-personal-reflection-on-listening-to-sounds-outside-of-our-attention/

with sounds & music by Pheobe riley Law & myself

photo by Pheobe riley Law from her 'desire lines' book

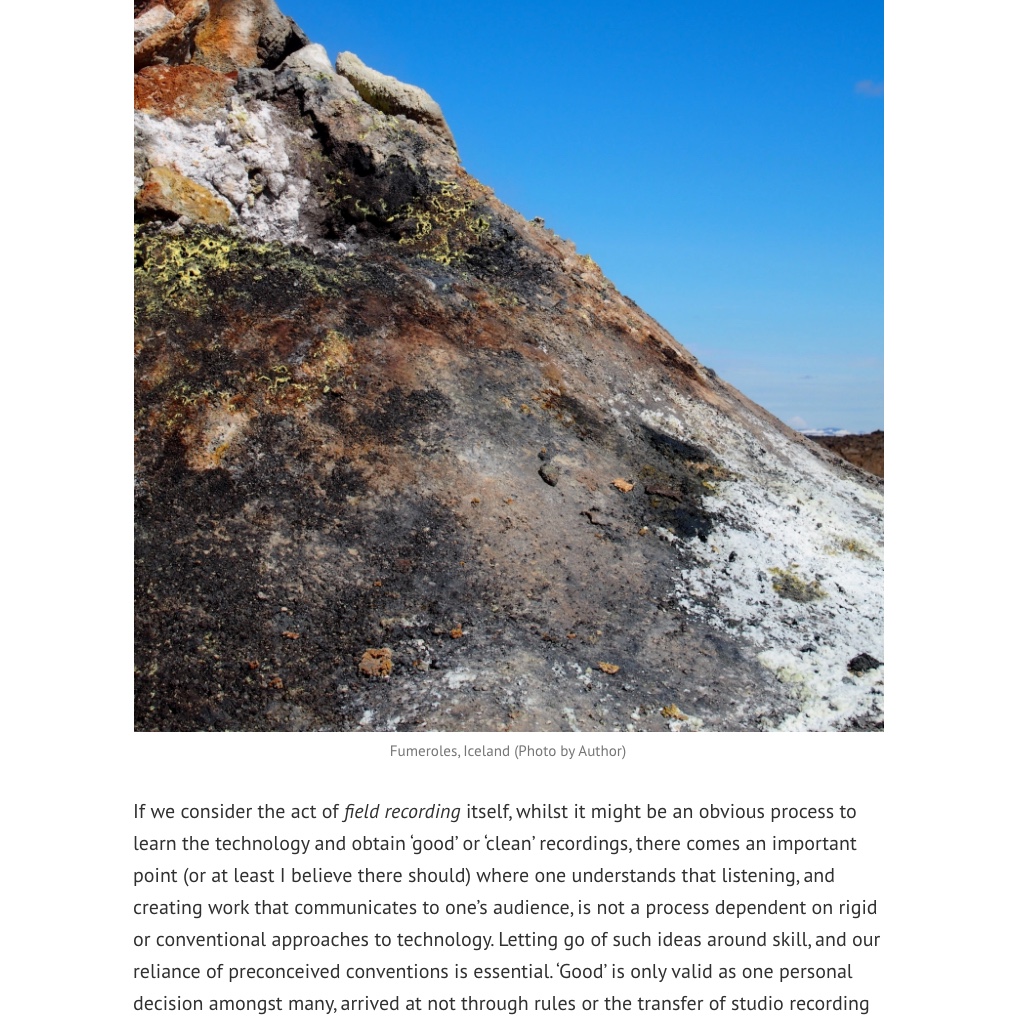

as part of ìsland | fjorar - the crystal detector for Cona / Steklenik / Radio Slovenia Ars, there is a pdf of texts on located sound / listening and materiality, scores and a QR code linking to a realisation of 'score for listening #100' by Pheobe riley Law & myself.

you can download it for free here

talking with Helen & Mark about ink botanic, dissolves, ants eating apricots, teleferica, ice, the sound of Japanese architecture and working with my daughter, Pheobe riley Law;

part one: BBC Radio Scotland Outdoors podcast

part two: BBC Radio Scotland Outdoors podcast

second text piece published in November 2020;

Migration between Nature and Listening - for the Land Lines project (Leeds Uni, Sussex Uni, St Andrews Uni)

https://landlinesproject.wordpress.com/migration-between-nature-and-listening-jez-riley-french/

listening > sound art > cinematic distortion' - published as part of the 'on chorus' project

https://on-chorus.com/?jez_riley_sound_culture

latest issue of Sonic Ideas Journal (Mexico) is now available, featuring some thoughts on the process of recording & reflecting on 'The Height of the Reeds' project for Hull, Capital of Culture 2017

https://sonicideas.org/mag.php?vol=11&num=21&secc=articles

a recent interview (June 2019) from The Sunday Tribune online:

TST: You’re known for working with field recordings and composition in a variety of innovative ways. How long have you been working in this field and what led you initially to work with sound?

JrF: I began with a cassette recorder my mum bought me for my 12th or 13th birthday, progressing to using reel-to-reel recorders & becoming interested in experimental music / sound. I took a break from my own work for much of my 20’s & early 30’s when I was running a music distribution business but since the late 90’s I have been working full time as an artist. My initial connection was simply that I thought of located sound as ‘music’ as I was too young to really understand or accept any borders between the two. I came to understand the differences of course but borders in any art form are still something I find problematic, mostly because they often enable elitism – however, there is a delicate balance between total openness and creative sincerity or tenacity.

TST: Are there any particular locations that have been particularly important to you in forging your aesthetic, and why?

JrF: yes & no. home & anywhere else with my daughter. I say this because I am, simply, me & I do what I do because it is part of who I am, not because it has been an attempt to have a ‘career’ in the arts, for want of a better way to put it. So, every aspect of life has forged my aesthetic in some sense. I am more affected by momentary situations or experiences.

TST: What is it about the process of sound that you are particularly interested in?

JrF: I could spend some time discussing the various elements but instead I think it is all contained in the statement above, that I am interested in the momentary, whether it be in terms of a visual interaction of elements or audible ones.

TST: It seems to me that one of the facets that your scores are interested in is the way sound travels in real physical environments, whether this is direct, looping on itself, dispersing or behaving in other ways that would have to be manufactured in the studio. Do you recognise anything of your work in this statement?

JrF: as the scores (scores for listening) are indeterminate it is, in essence, a collaboration between the scores themselves, my involvement and each person who experiences them. In that sense i’m not sure it is my role to recognise my intention in anyone else’s thoughts about them, if you see what I mean. I would perhaps though only say that I am of the firm belief that one elemental aspect of located sound (non-studio created or ordered sound) is that it cannot ever be recreated in a studio, not in any sense at all. That is one reason why it is endlessly fascinating – it is radically different every second & never fully repeats – some elements might but the combinations continue in constant flux.

TST: How is the natural world important in your work? Have you any recent projects or any coming up that intersect in particular with the movement or bheaviour of animals?

JrF: I’m on the side that rejects the definitions we have placed on ‘nature’, in so much as I believe we are simply another species & so I don’t separate an environment such as a forest to that of an urban location. Every place is different of course, at every time it is experienced, but I don’t have a border between ‘nature’ and ‘human’. In that sense all of my work is about ‘nature’, even when dealing with inanimate objects. I’m not a ‘sound collector’ so I tend not to have a motivation, aside from in documentary elements of projects perhaps, to plan what I might record. I listen to what is there, if i’m able (practically or in terms of how connected I feel to the process at the time) & that is what guides me.

TST: Photography is another art form that repeats itself in your practice. What for you is the relationship between photography and sound recording? How do you develop and work on your ideas in the two media?

JrF: I always ‘heard’ visual images and ‘saw’ sound. I don’t mean that I have some form of synesthesia, I mean that I was drawn to photographs as an element of sensory awareness. Early on, in my teens, I would experiment with soundtracking still images rather than films & I can’t really remember where that idea came from – I think probably a mix of healthy naivety and the specifics of exploring an art form without any formal education in it – after all if, at 13 or 14, no one has yet told you what a score ‘should’ look like you can see anything as one. Likewise I had no education about photography or other visual arts so I began by buying books in the sale sections or in second hand shops, which often meant avoiding the most famous names & instead stumbling across less mainstream or hyped work (which also often meant finding work by women more than men).

TST: What is your thought on music as a term and a concept? In general do you see music as being part of sound art or is the term irrelevant to how you view your work? Does the phrase sound art have a relevance?

JrF: I have two answers to this;

1) I didn’t accept the division when I first became aware of it in my early teens, but I also didn’t accept the way ‘music’ was increasingly separated from ‘the arts’ in the early 20th century, due in large part to the invention of affordable recording media & the growth of the entertainment industry element of ‘popular’ music. That said I know the various aspects that could be said to define each – even in the ways that are open to challenge.

2) ‘sound art’ as with any other term has problems. For example it is often used for work that is insincere or low quality ‘music’ with some bits of non-narrative sound added. It has become a sticker, a brand ident. In that sense it’s the same as any other term; there is poor work and good work.

TST: What other practitioners working in sound art today do you admire and why?

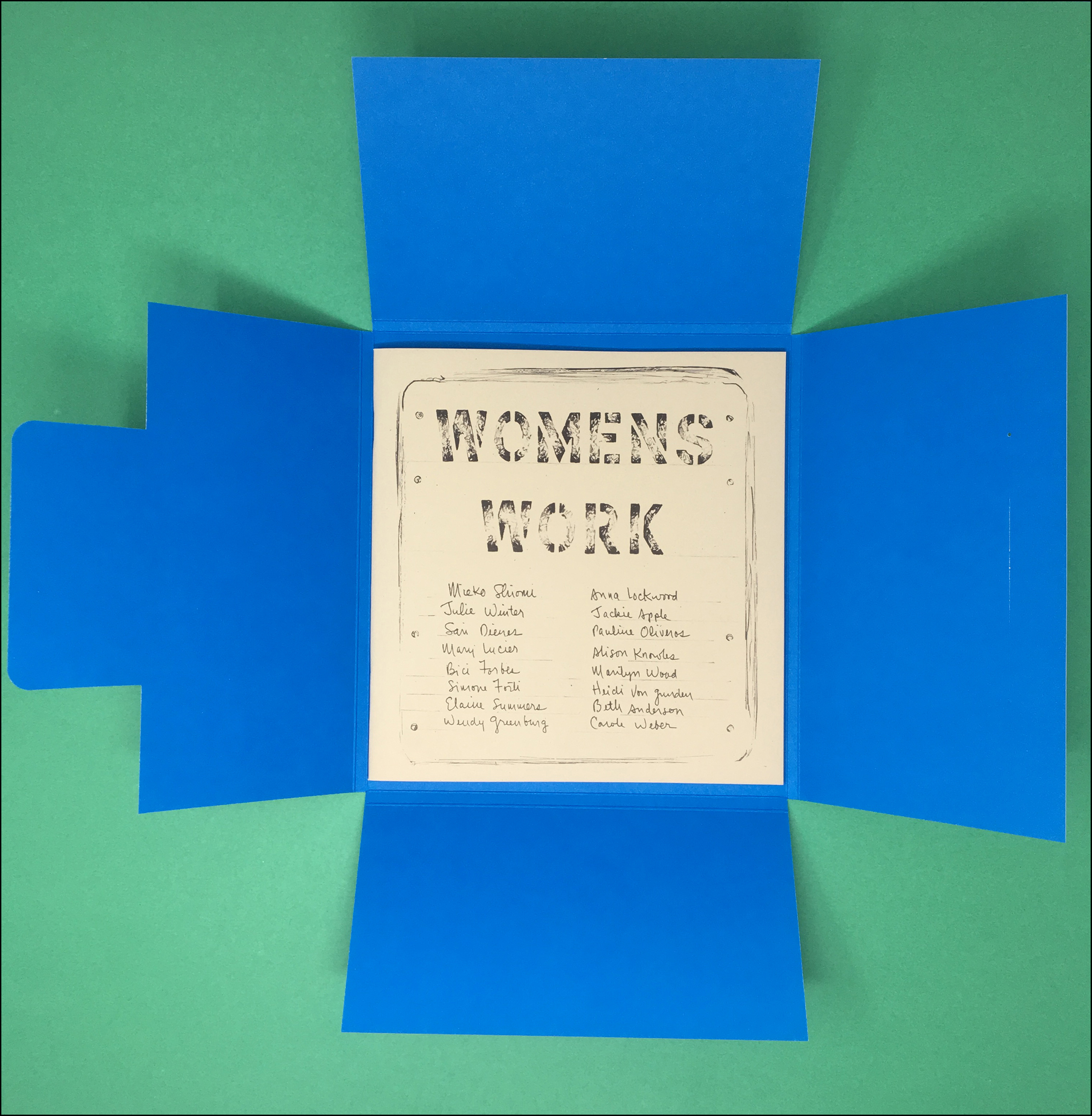

JrF: rather than mention individuals, of which there are lots of course, I think i’d prefer to answer this by saying two main things; 1) that I admire those who continue to create insightful, personal work in the face of prejudice, elitism, bullying, sexism etc. & I do not admire the work, however established it might be, that is created by those who display harmful attitudes towards others. This is not always an easy stance to take, as there are arguments for being able to separate the work from the artist. In critical terms I can do that but in terms of my personal interest I simply prefer to give my attention to those artists who don’t fall into cliched ways of being controlling towards others. Of course one doesn’t always know however. 2) in all honesty I would say that perhaps 80% of the work that I find most interesting is not by men working in these areas. Apart from any aspects of personal preference I think, generally, there are endemic reasons why men often create less interesting, critically speaking, work, including at a basic level an over dependance on certain ways of relating to technology rather than the material &, put simply (& I do think its very important for all men to realise this) that we have had it too easy for far too long in terms of access to opportunities and our distortion of & reference to ‘the history’. I believe those things are sometimes quite audible in the work, which isn’t to insult male artists, after all I am one myself & I know and admire lots of male artists, but we can’t pretend that most of us have had to have the same energy, the same determination, the same struggle to be heard. This is of course a very general comment – there are personal stories of struggle that inform the work of artists of all genders and those who prefer not to identify themselves in set ways. I guess what i’m trying to say is that generally the work I find has a wider range of elements and layers has always tended to be by women & that I do believe there are developmental issues with male art that have been influenced by the excesses of patriarchy…but this is a massive conversation, with a huge amount of nuance.

TST: I know you’re a supporter of women practitioners in sound art. Could you suggest three names of artists and writers about sound that I should investigate?

JrF: I, of course, actively stand against sexism & the negative effects of patriarchy in sound cultures, and elsewhere. I try to always work in ways that attempt to avoid some of the generic problems associated with certain male attitudes / histories, but that help, that work is to or for artists, many of whom happen to be women. So, yes, I am a supporter of practitioners in sound art who are women but I do that because I am interested in the work itself and the possibilities of access to creativity when any distortions are removed or challenged. Where I do specifically focus on the work of female artists then yes, I am deliberately choosing to do that & it is because I admire or respect the work itself; the need to redress the balance of the gender bias is one aspect but the work itself is prime. I have always, proportionately, been more drawn to work by women & that statement also needs some unpacking, which would take far too long, so I will simply say that I grew up (in terms of music & other arts) being interested in things outside of the standard ‘mainstream’, as I mentioned above, & that often meant that it would be work by women, work that was given less attention in certain quarters or was less easy to access outside of cities with well developed scenes. In that sense the development of an intuitive connection to creative work progressed within a growing knowledge of the role of women in the arts (a small example; I got bored very quickly with most of the male new wave & post punk bands, who seemed mostly to have a very narrow range of ideas. I only had pocket money back then so i’d tend to buy records that I thought looked interesting or where in the sale bins – these were often by women or female fronted bands, simply because in a provincial city in the UK music scenes were very conventionally male orientated – & almost always those records were unpredictable, more experimental and lyrically diverse). I also, for various reasons, confronted many aspects of male culture from a young age &, speaking very generally, this led me to be uninterested in work that conforms to or plays with stereotypical male traits (machismo, ‘dark’ aesthetics, technical obsession as a prop for ego etc).three names! that’s a challenge as there are 1000’s to chose from. So I have picked three that also illustrate some aspects of this discussion:

Anja Kanngieser https://anjakanngieser.com

Anja’s is one of those rare artists / researchers whose work seems to always offer up new layers, new triggers for connective thinking.

Jenny Hval http://jennyhval.com/

there are many reasons I like Jenny’s work but in this context I think she’s a great example of someone clearly caught up in the all encompassing energy of creativity – no borders, no constrains imposed by genre or art form.

Liz Phillips http://lizphillips.net/w/

apart from the sheer breadth of her work over many years there is an unfortunate reason for including her here; she is as good an example of how patriarchy has massively distorted the history of sound art as I can think of. She’s been at the forefront in terms of the work for decades, working with & alongside many of the well known male artists & yet I still come across people who don’t know her work – there is only one reason for that & it’s not the work & it’s not Liz. Search the various books or websites covering sound art for her name & you’ll very rarely find it – it will take anyone 5 minutes looking at her career to know that is a travesty.

& i’ll mention another, with a caveat, it’s my daughter. Pheobe riley Law http://www.pheoberileylaw.yolasite.com/

Of course i’m biased but what I think is relevant here is that I draw a huge amount of inspiration from seeing her work with sound in ways that remind me of the importance of being flexible and playful – not to be too precious about the material sometimes.

nice review from 'All about Jazz' by Henning Bolte of the set me & David Toop played at Punkt recently (translation errors corrected):

'A highly fascinating thing was the live remix of Arve Henriksen's 'Towards Language' by the duo of Jez riley French and David Toop. French, a sound artist working with extended field recording technique, is connected to Punkt via a sound project around the Humber Bridge of Hull for which he collaborated with Jan Bang, Arve Henriksen, Eivind Aarset and the Opera North earlier this year. They worked on the sound of the 2, 2 km long bridge, elaborating on it with the orchestra of the Opera North in the context of Hull as European Capital of Culture (together with Aarhus).

During the live-remix French left the stage shortly after the start of the remix he did together with David Toop. He left the stage to play the metal railings amplified by contact microphones. He had used those same railings before to record the 'input' of Arve Henriksen's group, filtered through the architecture of the building. That recording he left playing on stage along with one of the empty building resonating with the infrasound of its surroundings. It resulted in a highly fascinating sound flow and sound expansion that his fellow musician David Toop provided by extra layers, accents and highlighting. Actually French literally re-mixed the 'input' sound'

pleased to announce that the in-depth interview with myself by Mark Peter Wright for the British Library is now online. I am grateful to Cheryl Tipp at their sound archive and to Mark for the questions which allowed me space to talk not only about the sounds, but also about aspects of the deeply important personal elements of my work.

interview in Culture Vulture / Morning Star about Height of the Reeds:

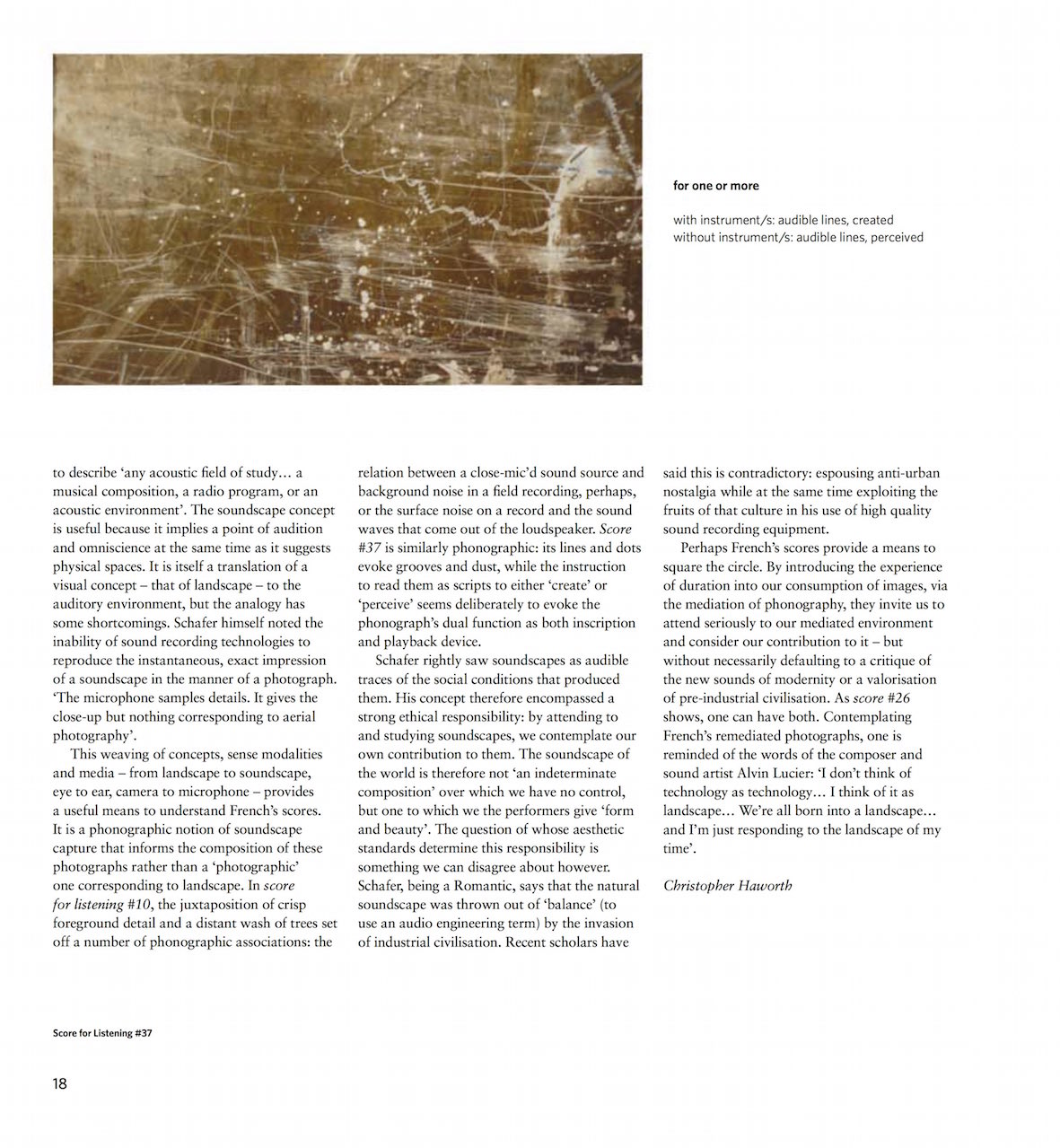

article on my work with photographic scores for 'Source' photography magazine

9 page booklet to accompany my piece for Tate Modern

article on my work for 'Inframedia' magazine

article for Rycote on my experience using their cyclone wind jammer whilst recording the reed beds of the river humber